Chapter 1

1

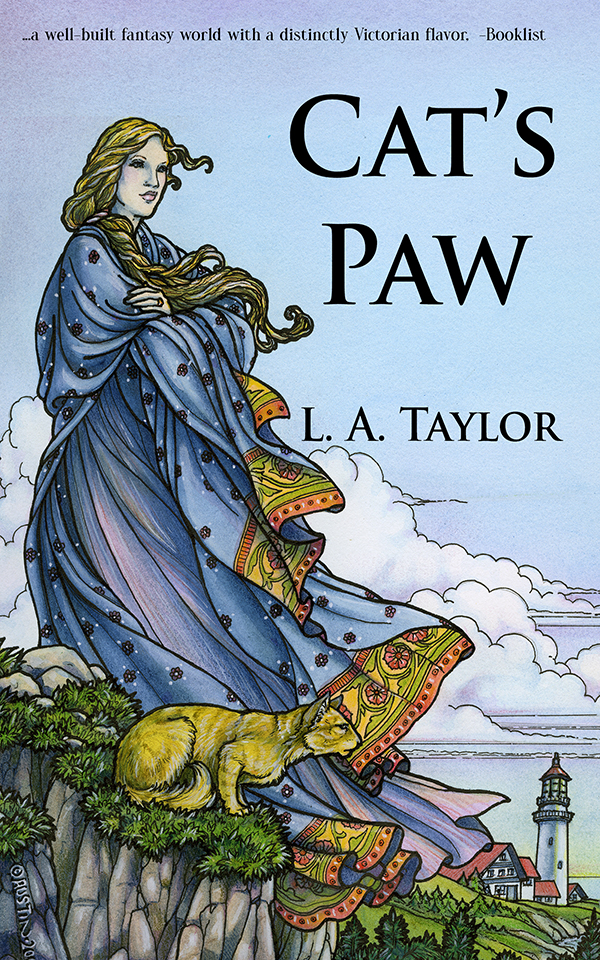

A ragged yellow cat was crouched on the library steps when Miranda leaned the door open against the wind.

The cat stood up and fixed its silver-eyed gaze on Miranda's face while she maneuvered herself and her books around the heavy oak door, then, seeming almost to nod, it trotted down the steps beside her. She turned toward home, heartened at the sight of the animal: a beast the color of polished brass, a streak of something like sunlight in the gloomy afternoon.

She needed that brightness, any brightness. Miranda pressed her lips together and faced the long black line of flagstones beside the road. Above it, the bare-branched elms made a tunnel of the narrow lane, their gray bark seeming almost to yearn toward the ground. Somehow the image drained her of spirit.

She had taken only a few steps away from the library when she heard a soft mew. Glancing back, she saw the cat staring after her with an intensity that struck her as more canine than feline. A brush of pity became a thought: Poor thing, it's homeless.

She abandoned the idea of rescue before it had a chance to shape itself. Her life had no room for another problem, not even the relatively minor one of settling a strange cat in with her own two resident royalty. She shrugged her hood forward, pulled her wool cloak more closely around herself and the books she carried, and trudged on. Dry leaves skittered past her ankles. A few snowflakes drifted out of the sky, whipped about or let hover until they touched the walk to lie poised an instant before melting.

Even snow would help brighten things up, Miranda thought, looking at the drab dead landscape, and felt a chill creep into her heart. No, snow wouldn't help. Snow wouldn't help at all.

From beyond the squat stone houses hunkered close beside the lane to her left she could hear the boom of surf and the clack and rattle of the pebble beach as the waves withdrew. The sound, as familiar as the pulse of her own blood, only darkened her mood. Three weeks, a month at most, and ice would begin to gather wherever the spray landed, the rocky shore become a gallery of fantastic blue-white sculpture.

And Alexi had not yet returned.

The road ended. The last of the houses beside it was dark: her good friend Evelyn wasn't home. Unfair, really, to bring her sorrows to Evelyn's door so often. . . . Telling herself she had no time to stop for a chat anyway, Miranda blinked away her disappointment. She passed by the house into the less effective shelter of the junipers that now bordered her path. Sparrows and chickadees had taken noisy refuge in the tangled branches, but Miranda scarcely noticed. She was too consumed with her thoughts.

A newly lean woman, no taller than average, she bent to the blustery wind with the hem of her cloak flapping unheeded. Her long face, with its angled planes, high cheekbones, and forthright nose was typical of this coastal province, as were her dark gray eyes and the hair once as golden as the cat that still followed her. With middle age she had become handsome. At the moment the wind had slapped her cheeks pink, making her almost beautiful. Had she known, Miranda would not have cared. Not without Alexi here to see her.

As she rounded the end of the juniper hedge a gust swirled her cloak out of her clutching fingers. The sea became abruptly louder: she had reached the end of the lane, where it turned into a broad-stepped path to the tower where she lived. Eyes drawn upward as always, Miranda saw the lighthouse beacon still unlit and hurried up the steps. Now she noticed the unusual silence of the gulls. They must be close to the water, expecting bad weather. The tide was high, the wind off the sea laden with spray. By the time she had climbed the fifty yards to her door, her cloak was heavy with damp and her face stinging. She shut the ancient slab of carved chestnut, grateful for warmth.

"Up, you, and move," she said to her younger son as she passed through the sitting room. "Your blood wants stirring, or it will all sink to your seat. Then where will your brain be?"

"In my head," Steth said mildly, his eyes still on his book.

"Up, up, up! You've been there all afternoon!" Miranda set the library books on the table under the kitchen window and took off her wet cloak. She draped it over a chair to dry and combed her hair with her fingers, going back to the sitting room door to ask, "Where's your brother?"

"Gone up to light the beacon."

"It wasn't lit when I came up the path."

Steth yawned and put a finger on his place. "That's what he said he was doing," he said. "What's for supper?"

"I'll think about that in a minute. First I'd better see to the beacon. I think we're in for a storm." She opened the door at the bottom of the winding tower stairs to call, "Hathden?"

An incomprehensible reply floated down to her.

Miranda sighed and started up the steps. As she climbed, the stairwell suddenly brightened and a low whirring noise began: Hathden had turned on the light. One of Miranda's newest problems was that the beacon's automatic switch had failed last week, meaning that someone had to be home when dusk fell or when storms darkened the sky. She had examined the failed switch, had even taken the casing off and seen what controlled it. An arrangement of thin, overlapping metal leaves formed an open circle that should adjust to let a constant amount of light fall on a sensor plate behind, much like the pupil of an eye. When the leaves opened widest, the switch was tripped. But Miranda had seen nothing wrong with the workings. To be honest, she had not understood exactly how the thing was supposed to work. Alexi was the one who knew how to fix the lighthouse gadgets. A twinge of worry cramped her belly at the thought.

She reached the top of the steps. Over her head the beacon rotated on well-oiled gears, its brilliance shielded from her eyes. Huge windows began just above waist level and angled outward to the roof, held in place by narrow strips of stonework reinforced with steel—and, legend had it, a good dose of magic. Miranda trusted the steel. She was inclined to chuckle at the very idea of the magic. Even if such a thing did exist—a possibility she was not prepared to entertain seriously even for a moment—didn't the old tales say that a spell did not long outlive its caster? And no one could have renewed this magic lately . . . although, Miranda reminded herself with an echo of her usual humor, Lexi did seem to have a magic touch with the workings of the beacon!

She found Hathden kneeling at the broad windowsill, his chin on his folded arms, looking out to sea.

"Hi," she said. "What's up?"

"Nothing."

"Thanks for lighting the beacon."

Hathden said nothing for a moment. Then he stirred and said softly, "It's mine to light now."

"Hathden, no! It's just until your father comes home."

Without turning, Hathden said, "He hasn't been home since midsummer. He said the job was dangerous the day the letter came from the Governor asking him to do it—whatever it was. We've had no word from him or from anyone else since long before the leaves turned and now it's winter, or nearly."

"Your father will come home," Miranda told him fiercely. "I know it."

"You wish it," Hathden said, still gazing out the window. Tarnished pewter sky and peened pewter water merged in a horizon made uncertain by dimness and distance. Closer at hand, the white scum of seafoam and gulls danced over the waves. Closer still, the intense beam of light turned the sparse snow into a whirling glitter. Miranda, grasping the handrail, backed down two steps instead of going up to the windows to peer down at the foundation of rock beneath her as she usually did. The stone wall was cold beside her.

"I wish it, too," Hathden went on. "But we have to be sensible. I'm keeper of the beacon, now."

"Can you fix the switch?" A vicious question. Miranda was sorry the moment it left her mouth.

"I'll find out how. Someone must know." Hathden stood up, at last, and looked down at her. His face was his father's made young. So very, very young—but older than Alexi's had been when they had first met. "It's not as if the trade were secret, like the dyer's or jewelsmith's." Hathden shrugged. "It's just ours."

Ours. Hathden's and Alexi's and the men of the Glivven line, back and back for so many generations Miranda always felt a kind of awe at the thought of them, back even as far as the days before what some people thought had been magic was outlawed, when some poor fool might have mouthed a rhyme in the Elder Speech and thought that by doing so he had put a spell on the tower to keep it safe in a wind like this. If it was still the same tower, as Alexi maintained and Miranda doubted—although she had to admit that the stone steps had developed dips in their centers that suggested centuries of use.

"I'm going to start supper," she said, to bypass whatever Hathden might have to say next. Seventeen years old, a lightkeeper? "We'll talk about this later." Her feet striking an even beat on the worn steps as she descended, Miranda tried to imagine Hathden grown to manhood, and could think only that it was impossible for so many years to have passed since she had first seen him, red and wrinkled and bawling and streaked with her own blood. She had been twenty, Alexi three years older.

"Take your nose out of that book, Steth, and come give me a hand with that supper you're so anxious about," Miranda ordered when she reached the bottom of the stairs. She went into the kitchen, took a skillet off its hook, set it on the stove, and stared at it.

No matter that I haven't learned to cook for three instead of four, she told herself. The boys eat everything but the bones, and the cats gnaw those.

"Steth!" she called, turning angrily toward the sitting room. The boy was standing right behind her. As he began to protest, she heard Hathden coming down the stairs.

Somehow, she and her sons would manage. Until Alexi came home.

2

For years, Miranda had slept with the pulse of the beacon at her shutters, but this night the regular brightening and dimming of the room made her restless. Again and again she rolled drowsily toward Alexi's side of the bed, waking when she found it cold. Nights were when she missed him most.

The wind muttered in the chinks of the stone tower, phrases in which Miranda could almost make out words, as years before she had almost been able to hear a child crying distantly, although he slept in the cradle at her side. First one cat, then the other, came and curled up on Alexi's side of the bed. Reaching for the nearest, she curled herself around the warm fur, getting a half-hearted purr in response. No cat could substitute for the warmth of Alexi's back against her own. Still, she must have slept, because what seemed a moment later she stretched to find both cats at the foot of the bed.

As had happened so often since his letters had stopped coming, Miranda dreamed of Alexi. But this time she dreamed that she was Alexi, crouched on all fours in a space too low to allow him to stand, looking out upon a bleak world of cold stone and dead flowers. Again she woke, again lay listening to the dark wind blowing with the cry of a child, or a cat, and she shivered.

Snow spattered against the glass beyond the shutters; the room softly brightened and softly dimmed. Morning would come. Morning always came. And Alexi?

remembered his wry smile the day he left, his comment that she'd find this job—what was his exact word? Not silly. Preposterous, that was it. Preposterous, but dangerous. He hadn't said why: like other, smaller "jobs" he'd done for the Governor, this one was secret. Alexi was good at some kind of investigation, Miranda had gathered over the years, and once in a while he was needed.

As always, he had checked all the mechanisms of the beacon, before leaving her and the boys in charge of it, so that it would need no great attention from them. The windows would have to be cleaned, inside and out—a balcony around the tower could be reached from a door on the landward side, although whether one could properly speak of a "landward side" on a narrow promontory like Gwynnhead was something Miranda had teased Alexi about for years. Hadn't Alexi said that he'd hoped to be home in time to help? But they'd washed the windows four times since he'd left.

Letters had come twice a week for almost two months, reassuring and humorous as only her Lexi could be. Then nothing. In the morning I'll get his letters out again, Miranda thought, and read every last one yet again for a clue, a code, even, something to tell me what has happened.

She slept again, and woke in the fresh light of dawn.

Steth, as always, was hard to wake, but Hathden wasn't even in bed. Miranda found him in the kitchen, stirring oatmeal into a pot of boiling water.

"Good morning," she said. "You're up early."

"Couldn't sleep." Hathden set the spoon down and put the lid on the pot. "It snowed a little last night," he said. "Did you see?"

"No, I haven't looked out yet."

me to sweep the steps before school?"

"Leave them for me," Miranda said. "I need the exercise."

Hathden gave her an odd glance. "That's right." He nodded. "It helps settle me, too. But I'll have a walk, I guess, going to school." Miranda hugged him as he stood at the stove, wishing guiltily that it could be his father she hugged instead—or rather, in addition.

"Steth up yet?" Hathden asked.

Miranda went back to the kitchen door to call her fourteen-year-old. She didn't quite know what to make of Hathden in his new, somberly adult frame of mind. It'll work out, she told herself, bellowing, "Steth?"

Hearing the jingle of the bells on the postman's horse later that morning, Miranda went to the door. The steps had garnered a thin shell of snow overnight. In it, she saw catprints: not from one of her own cats, but from one with an extra toe on each foot. She put on her cloak and grabbed the broom to sweep her way down the many steps to the base of the hill. The catprints were only on the top two steps. Miranda recalled the crying wind of the night before. Had it really been a cat, freezing in the storm and pleading for warmth?

The idea saddened her as she worked down the hill. Nothing in the mailbox at the bottom of the hill improved her mood: a bill for lights and one for water, a notice from the library about the overdue book she had returned the afternoon before. No answer to the letter she'd written to the Governor, asking for any news. Above all, nothing from Lexi.

She climbed the steps to the house feeling weary, early in the day as it was. The gulls were crying today, the air salty, but neither well-worn sound nor well-worn scent lightened her heart as they usually did. She opened the door. A streak of gold shot past her into the house. That cat!

"Hi!" she shouted. "Come back here!" Tail high, the beast vanished into her kitchen. Expecting an instant explosion of snarls and shrieks from her own cats, she ran after it, then stopped, astonished. Mrs. Putz and Tomtom sat, one at each side of the mat on which the cat food dishes lay, while the golden cat ate. They gazed at the invader with interest, but no animosity.

Miranda plunked down at the table, still holding the broom. "Well," she said, after watching the beast polish both dishes with an eager tongue. "I guess you have a home, after all."

The cat turned at her voice, came toward her, and rubbed its head against her shins. Miranda could have sworn it was smiling.

Over the next week and some, winter, having given fair warning, retreated. Hathden took over the lighting of the beacon.

Miranda watched her son's absorption in his self-imposed task with a mixture of pride and panic. Even at seventeen he was a responsible lightkeeper: the day after their conversation in the tower, Steth came home from school alone, saying that Hathden had stopped at the library to see what he could find out about automatic switches. Just before dusk Hathden arrived and went up the tower steps after the briefest of greetings.

"Did you find anything?" Miranda asked when he came down.

"No."

"I guess we'll just have to keep turning the switch by hand, then," she sighed.

"I'm going to ask Andreu if he can do anything," Hathden said. "I'll stop by his

house on the way to school tomorrow."

Old Andreu, the village handyman, came to the door the next day. He went up the tower steps,

grumbling at the long climb.

Still grumbling, he took the casing off the switch to poke at the innards, knotted his shaggy gray

eyebrows together

for at least half an hour while Miranda waited with clasped hands for his verdict, and went away

scratching his head.

"Did Andreu come?" Hathden asked the moment he walked through the door that afternoon.

Miranda nodded. "He couldn't fix the switch, though. He couldn't figure out how it worked."

"Andreu couldn't?" Hathden echoed, sounding as surprised and disappointed as Miranda had been. She shook her head. "I guess I'll have to think of something else, then," Hathden said.

Miranda, hearing a mew at the back door, opened it. A parade of three cats entered. She stood in the doorway a moment, watching the flash of the beacon on the narrow band of coarse grass between herself and the fenced edge of the cliff. "What about asking Master Craffid to look at it?" she suggested.

"I guess I could do that," Hathden agreed. Miranda closed the door against the cool air and returned to the kitchen table, to help Steth draw some geometry problems.

The next day Master Craffid, the science teacher, came home with Hathden to look at the automatic switch, examined the instrument carefully, and declared that not only did it not work now, but it could never have worked in the first place.

"That's absurd," Miranda said. "It's been working perfectly well for years."

"How?"

"I don't know. That's why we asked you to help."

"I'm sorry, Mrs. Glivven. There's just no way on earth that switch could have operated," the man insisted. "Not as it is now. You're sure you haven't removed some part?"

"Quite sure," Miranda said, looking thoughtfully at Hathden, who shook his head. Maybe Andreu had left something out when he reassembled it? Dare she insult him by asking? The science teacher went home, and at twilight Hathden climbed the stairs to turn the beacon on, refusing Miranda's offer to do it.

When she went down for the mail the next morning, to find nothing in the box but a card from a friend who had moved to the mainland a few years before, Miranda knocked on Evelyn's back door.

"Come in," Evelyn said, searching her face. "I'll put on the kettle."

"Oh, that would be wonderful." Miranda sat at the kitchen table and showed Evelyn the card.

"Did you get the switch fixed?" Evelyn asked, nodding and handing the card back. "I saw Mikkel Craffid coming down your steps yesterday afternoon."

Miranda shook her head. "And Hathden insists on turning the beacon on himself," she said. "Oh, Evvie! He thinks Lexi's dead—that it's his job now, forever."

"Shh," Evelyn soothed.

"It's hard to see him grow up so young," Miranda continued. "And I won't believe that Alexi's dead!"

Evelyn looked out her kitchen window to the hill and the tower rising above the village. "Still nothing, then."

"You'd have heard," Miranda assured her. "I wouldn't even go up to the tower from the mailbox! I'd run straight over here."

The kettle began to sing on the big iron stove. Evelyn fetched it and poured boiling water into the teapot. "Where was he, last you heard?" she asked, returning the kettle to the edge of the stove. "Bierdsey, wasn't it?"

Miranda nodded.

Evelyn got two mugs down from a shelf and set them on the table. "Why not go look for him?"

"It's so far!" Miranda sighed. "Two days by train, with a change overnight at Clunn. That's four days just traveling there and back, and who knows how long to look for him?"

Her friend sat down and poured tea into the mugs. "If it's money . . ." she said slowly.

"No, no. It's the light," Miranda said hastily. "Someone has to see to it, every day."

"Hathden's doing that," Evelyn pointed out.

"Evelyn, people's lives—-"

"Depend on the light, I know. Don't you think Hathden does, too?"

Miranda sipped at the hot lemony tea.

"Would Hathden let down the whole line of Glivvens?" Evelyn asked. "Not for a moment. You know it, Miranda."

"True."

"Besides, David and I are here, a stone's throw away. One of us can always run up to the tower and prod the boys." Evelyn gave her a sideways look. "We come of sailors, remember," she added, an oblique way of assuring Miranda she wouldn't forget.

Miranda nodded.

"If it's housework and eating and such that worries you, they can eat here, or I'll make sure they have food in the house. How much of a mess could they make in just a few days?"

"Oh, they're neat enough, for boys." Miranda sat looking at her mug, worrying. Suppose she did go? Would Steth do his schoolwork? Would the beacon always be lit? Would . . .

"I could look in on them," Evelyn went on. "Make sure they have clean clothes, if you're gone that long, and nag Steth about his homework—-"

"That would be a help," Miranda admitted.

"Good heavens, Miranda, they're fourteen and seventeen! In the old days they'd have been out on their own at their ages. They can manage without you, or me either, for that matter, though I'm glad to keep an eye on them."

"I suppose you're right," she said unhappily.

"You're afraid of what you might find in Bierdsey, aren't you?" Evelyn reached across the table and clasped Miranda's hand. Her fingers feel so warm, my own must be icy, Miranda thought. She nodded.

"But isn't it worse to wait here, day after day, hoping for word and knowing nothing?" Evelyn pursued.

After a moment of anguish Miranda nodded again.

"Think about it," Evelyn said.

She didn't want to think about it. She didn't want to think about anything ever again. But somehow, half an hour later Miranda had decided to go. She climbed the hill to the beacon house clutching the edges of her cloak to pull it snug. Two years had passed—or was it three?—since she had crossed the causeway from the village to the mainland on her own. Too long. Time for an adventure. But her adventures had always been shared with Alexi. . . .

She waited until after supper to announce to her sons that she was going to search for their father. Hathden looked almost relieved. Steth was openmouthed with surprise.

"Where will you look?" Steth asked.

"I'll start by going to Bierdsey, since that's where his letters came from." Miranda scraped a plate into one of the cat food dishes. Three small heads crowded around it, munching contentedly. The golden tomcat glanced up at her. It had plumped up well since adopting her, she noticed. Its coat was thick and sleek, and the bumps of its backbone hidden.

"Then what?" Steth asked.

"I'll go to the inns and see if he stayed in any of them, and if I find that he did, I'll ask whether he said where he was going when he moved on, I guess."

"That sounds like a good plan," Hathden agreed.

"I'll be gone at least five days, probably a lot longer." Miranda shoved Mrs. Putz out of the way with one foot and scraped the last plate into the dish. The cats moved back into position. "Are you sure you can tend the light absolutely without fail and keep up with your schoolwork?"

Hathden made a faint sound of assent. Steth groaned, "Oh, Mother!"

"Evelyn says she'll feed you, if you want, or help you with the marketing," Miranda went on. "I'll have to catch the train at Gwynn-on-the-Main, and change at Clunn. Perhaps Andreu would be willing to drive me over the causeway."

"When will you go?" Steth asked.

Miranda hesitated. She hadn't thought that far ahead.

"Tomorrow," Hathden said.

"Tomorrow! Oh, no, not that soon. I'd never get packed in time," Miranda protested. "I haven't stocked the pantry for you, or—-"

"I'll go right now and ask Andreu if he's willing to drive." Hathden took his cloak from its peg beside the kitchen door. "We can shop for ourselves, if you'll leave us some money. The bank will be open before you have to leave, so you can get some cash and some letters of credit."

"Hathden," Miranda said suspiciously. "How have you thought of all this so quickly?"

The boy shrugged into his cloak and fastened the closure. "I've been wanting you to go look for Father for weeks, but I was afraid you'd say no. So I thought it all out, but I didn't know how to go by myself without stealing the money."

"I see."

"And there's the light. I can't leave it." Hathden opened the door and stepped out.

"We'll be fine," Steth said. As if to prove it, he went into the sitting room and fetched his sack of schoolbooks. Miranda sank into a chair at the kitchen table. The golden cat leaped into her lap and settled down. She stroked it absently.

Funny that it never purrs, she thought.

3

The next morning was a whirl of arrangements—friends to be told she was going and farewells to be said, the bank, a visit to the school to tell the provost Hathden and Steth were on their own for a few days. They'll be all right, Miranda admonished her doubtful self, looking back at the school after saying good-bye to her boys. In a village of three hundred seagoing people, everyone was sure to look out for the lightkeeper's sons.

She returned home, breathless from her fast climb up the steps, and finished packing under the eye of the nameless yellow cat. She lugged her case to the front door and looked around the sitting room flooded with sunlight, sunlight that picked out the loose threads of the worn chair cushions on which she and Alexi had sat so many evenings, sunlight that glinted from the touch-polished wood of the chair arms. Twelve good years spent here, Miranda thought. Ever since Alexi's father had drowned, when he was out in that storm with the lifeboat, trying to save four sailors who also had drowned. . . .

She shuddered. And even before that, she had known this room well. Had known it almost as long as she could remember. How could she bear to leave it?

A knock interrupted her melancholy thoughts. She opened the door to Andreu. "Morning, M'randa," he said. "Ready to go?"

"Yes, my case is right here." She pushed it forward.

"I'll carry it down for you."

"Thanks." Miranda took one more long look around the room. As she did, the yellow cat trod deliberately out of the kitchen and across the sitting room. She let it go through the door. With its fine thick coat of fur it wouldn't be chilled before the boys got home from school to let it in, and it could always find itself a sunny spot to lie in.

Andreu had already reached the wagon that was sitting at the end of the lane. Miranda closed the door with an extra caress of farewell, saw Evelyn standing beside the horses ready to wish her good-bye and good luck, and swallowed her panic.

As she started down the steps, the yellow cat appeared from around the corner of the house and twined between her feet, looking up at her as she tried to avoid tripping on it. She bent to pat it and went on down the hill to join Andreu and Evelyn at the wagon.

"My, you look wonderful," Evelyn said. "This is doing you a world of good, Miranda."

"I suppose so."

"You know it is." Evelyn squeezed her tightly. "Good-bye, sweet, and good luck."

Miranda climbed onto the wagon, blinking away tears and trying to smile. She looked down at her knees: she was wearing her very best winter clothes, a pair of dark green wool trousers embroidered with flowers in pale blue and purple, a long-sleeved purple tunic with a band of embroidery around each cuff to match the trousers, and her best high leather boots. She'd thought the clothes, even as loose as they'd become recently, would give her confidence, but now she could only think that in Bierdsey they would look horribly provincial.

Andreu shook the reins and she was on her way. The wagon jangled down the street, past the library, the three shops at the heart of the village, and on past the school. A gust of wind caught at her cloak as they started onto the causeway.

The golden cat darted ahead of them. "Looks as if Gwynnhead is losing a citizen," Andreu remarked. "B'longs to someone, by the look of it, though I can't just bring to mind who."

"Oh, dear," Miranda said. "It's mine—that is, it strayed into my house a week or more ago, and no one's claimed it."

"Pretty creature," Andreu said. "Should we stop and take ëim back?"

Miranda pulled her watch from her tunic pocket and cast a worried glance at it. "No," she said. "I might miss the train. If we can get it into the wagon, would you mind taking it back?"

"Glad to. Hold the reins and I'll see if he'll come to me."

It crossed Miranda's mind that if Andreu didn't recognize the cat, then it might have wandered onto Gwynnhead from the mainland and now simply be on its way home. But, to her surprise, when the horses pulled up the animal jumped onto the wagon and into her lap, where it settled down and craned its neck to see forward.

Gwynn-on-the-Main was a half-hour drive inland over a gravel road, protected from the sea wind by a line of low hills. The trees here struggled less than those on the headland: a group of oaks beside the road grew straight and tall, and the archway of elm branches over them as they approached the town was far taller than the one over Gwynnhead's single street. Blooming snapdragons still stood in some dooryards. Even a few chrysanthemums flaunted their bright rusts and yellows here and there, despite the hard frost of three weeks before. A woman pulling the last of her garden beets waved to them as they passed, and the sun was warm on their backs.

Miranda felt her anxiety changing to anticipation as Andreu turned the horses toward the train station. The low stone platform, half roofed over, and the little box of a ticket office soon came into view. Andreu drew up close to the platform and hitched the horses to an iron ring set into the stone.

"We'll be just in time," he said, reaching up to give Miranda a hand down from the wagon. The cat shifted, but wouldn't leave her lap. She scooped it up with one arm and climbed down, the cat clinging to her shoulder with one spread paw. "You'd best run and buy your ticket," Andreu told her. "I just heard a whistle."

Miranda hurried into the tiny station and bought a ticket for Clunn. She met Andreu on the platform and looked down the track for the train. "Yes, there it is," she said. "We weren't a moment too soon."

"Good thing we didn't go back," Andreu agreed. The train chuffed into the station and stopped with a clanging of metal and a loud hiss of steam, the bell at its side ringing. Miranda held tightly to the cat to keep it from dashing under the huge iron wheels.

"Good luck, then, M'randa," the handyman said.

"Thanks. I think I'll need a lot of good luck," she replied rather forlornly. The idea of going to as large a town as Bierdsey scared her. How lucky she was to live in a tiny village where she had a place in life without asking! She smiled at old Andreu, feeling a flash of affection, and stood on tiptoe to brush a quick kiss across his cheek. The golden cat twisted and slipped from her hands.

"Hi," she yelled. "Come back here!" A streak of gold disappeared behind a luggage cart. The trainman was calling for passengers.

"Never mind that," Andreu said. "I'll catch ëim and take ëim home for you, don't fear. You board that train, or it'll leave without you!"

Miranda climbed the steps. Andreu had to trot beside the already-moving car to hand up her case. The trainman helped her get it aboard and settled in the luggage rack at one end of the car. Miranda balanced herself carefully to move along the aisle of the car and found a seat near a window. Andreu was already too far behind to wave to.

One step at a time, Miranda told herself. She was on her way to Clunn. There, she'd find a room for the night and take the morning train to Bierdsey, and then . . . what?

About fifteen minutes later, while she was watching the landscape glide past at five times the speed of old Andreu's wagon, she heard a prrrt beside her and looked over. The golden cat had jumped onto the empty seat and now stepped a tentative paw onto her thigh.

"Well," Miranda exclaimed. "How did you do that?"

The cat, by this time in her lap, merely folded its paws beneath itself and let its eyes close. Miranda stroked its ears. "You seem to have chosen to come wherever I go," she remarked to it. No doubt at all, it was nice to be chosen, even by a cat. I should name it, she thought. But its coat was the color of her husband's hair, its eyes were almost the same iridescent gray as her husband's eyes. The only name that came to mind was his.

Rational skeptic she might be, but coincidence still had the power to send a shiver down Miranda's back. The cat glanced up at her with its odd appearance of smiling, fitted its head to its forepaws, and went to sleep.